Where Afghan law fails women

Afghan women have come a long way since the dark days of the Taliban regime. Yet a key obstacle to this progress continues to be high levels of violence against women.

The legal system has failed to protect women adequately when it comes to some of the most common crimes against them; rape, domestic violence, underage and forced marriages.

That is why, in 2009, a number of prominent Afghan women’s rights activists, members of civil society groups, and some lawmakers came together to draft a bill to better protect women through legal channels and to define crimes of violence against women. The bill, known as The Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) Law, was decreed into law through an Executive Order by the former Afghan President Hamid Karzaion, on July 20, 2009, while parliament was in recess.

During such periods, the Afghan Constitution allows the president to issue decrees for emergency purposes, but the Constitution also requires such decrees to be forwarded to parliament for approval. Some women activists nonetheless suggested that it was not necessary to send the EVAW law to parliament.

Political climate

Others, including myself, argued that although the Executive Order on EVAW was a significant step in the battle for the elimination of violence against women, the law remained vulnerable to being reversed by a new president. Indeed, presidential elections were just around the corner.

As the drawdown of the international troops drew nearer, we feared that the political climate would make it increasingly difficult to get the law anchored in parliament. In addition, we feared that any peace talks with the Taliban could end up sacrificing EVAW in a bid to appease the militants. Securing parliamentary approval for the law would give us much stronger ammunition in protecting it against extremist attacks.

In order to get an agreement on the EVAW law in parliament, we worked tirelessly for months, using three main strategies. Firstly, we started a lobbying campaign with those who opposed the law, mainly conservatives.

Secondly, we went to visit them in their houses, explaining the law to them article by article to obtain their signature in support of the law. We also organised exchange visits for conservative MPs to other Muslim countries so they could explore how these countries had been enforcing similar legislation for decades.

Finally we worked through the joint committee in parliament for more than two years to develop a consensus on the law and defuse the opposition of conservatives. In late 2009, there were only two issues left where conservative MPs did not agree.

These were the law’s punishment of relatives for underage marriage and for polygamy under certain conditions as well as the fact that women’s rights advocates wanted to include “honour killings” as a specific crime in the law.

At this point, however, MPs became increasingly preoccupied with the then-upcoming parliamentary elections scheduled for Spring 2010, thus the process lost momentum.

Unfortunately, after the 2010 parliamentary elections, we ended up with a more conservative parliament. Contested election results left the new parliament paralysed for almost a year. As a consequence, discussions about the EVAW law only resumed in mid-2011.

At this time the draft was re-sent to the 18 parliamentary commissions. All but one of the commissions agreed with the text of the law or presented constructive suggestions. The final commission, the legislative (Taqnin) committee, headed by the foremost opponent of the EVAW law, submitted 34 pages of suggested amendments.

Some of these suggestions were helpful and were duly included, such as a proposal to have specialised prosecution units in all of Afghanistan. As before, we rejected the proposals to leave underage marriage and the contraction of invalid polygamous marriages as non-punishable acts. We similarly rejected a new suggestion which was to close all women’s shelters and arrange for the victims of violence to stay with relatives instead.

Opponents to the law

Although the opponents were vocal, they did not outnumber the rest. What was damaging, however, was an unhealthy political rivalry that ensued among mostly female parliamentarians and supporters of EVAW. Some progressive women’s rights activists, including some from international organisations, argued that the time was not right to pass the EVAW and that it should be left as a presidential decree.

There were good reasons for seeking parliamentary approval. Yet some of my colleagues began accusing me of using the bill to further my own political career and gain support for my assumed ambitions for the 2014 presidential elections.

Instead of supporting EVAW, many female MPs stood silent during the parliamentary debates on the bill and some even went as far as to lobby against it. As a result, when the law was presented to the plenary in May 2013, conservative MPs who were opposed to EVAW were further emboldened.

The new Speaker of the House did not hold a lot a lot of influence and probably, for that reason, did not back the bill either.

With the conservative MPs entrenched in their opposition to EVAW, a weak speaker and a lack of support from my fellow female MPs, the EVAW bill failed to pass.Those of us who saw the passing of EVAW to be beyond politics, and understood its importance for tackling violence against women, were left heartbroken.

With the international community now gradually disengaging from Afghanistan, time is running out for Afghan women. We have made important gains since 2001, but we need the force of the law behind us to sustain our achievements.

We need to arm ourselves with solid laws like the EVAW law to fight the violence and other ills of our society which are destroying the souls of our sisters across the country. The fact that the EVAW law has not been approved by the parliament is the reason for its weak implementation rates; many justice officials are questioning the law’s status and therefore do not apply it.

One promising thing on the horizon is that we now have a president and chief executive who both understand the multitude of challenges facing women. I would like to take this opportunity and call on President Ashraf Ghani and our Chief Executive Dr Abdullah Abdullah to declare their support for the passage of the EVAW bill.

I also call on my female colleagues in parliament and all Afghan women rights activists and our international partners to set aside their differences and join us in support of the ratification of the bill. As the recent parliamentary approval of the BSA shows, when the government and others make something a priority, the conservative MPs can be isolated.

Times may be difficult now for Afghanistan, differences may be wide and security challenges are growing, but failure to back the EVAW and allowing it to die will deal a severe blow to Afghan women’s rights.

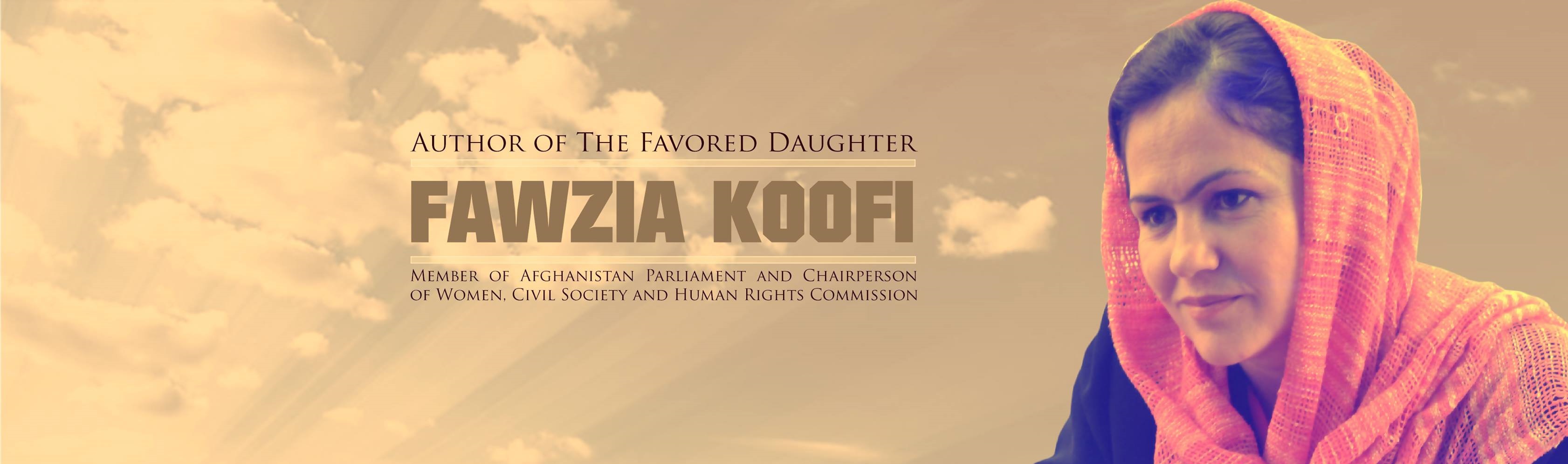

Fawzia Koofi is an Afghan politician and women’s rights activist. Originally from Badakhshan province, she is currently serving as a Member of Parliament in Kabul and is the Vice President of the National Assembly.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.